One concern I've had with writing

Maximum Recursion Depth is that while it utilizes elements from Buddhism, Taoism, and Chinese mythology, I am not an expert on these subjects, nor do they reflect my personal lived experience per se; rather, what I've tried to communicate, is that within the game, these ideas have been filtered through my actual personal, lived experience. I've gone out of my way, such as in

my interview at The Hardboiled GMShoe's Office, to make this point, and to highlight elements of the setting that are separate from these influences (such as the

NY Factions and

Weirder Factions blog posts).

That being said, I think it would be disingenuous to ignore these connections altogether. So I want to talk about some of the ideas from Buddhism, Taoism, and Chinese mythology that influence the setting, why I chose to use certain terms but not others, how I'm interpreting those ideas, etc. Again, I want to reiterate, I am not a scholar on these topics, they are not my lived experience, this is not intended as a thorough, scholarly reference; these are just my personal interpretations. This is also a non-exhaustive list. I may add to it or edit it. I will almost certainly forget stuff. There are things I reference here that I have little more to say about at the moment besides "I read this, it probably influenced me, but I don't remember the particulars". Also, the items in this list are in no particular order. There are also plenty of other books of science and philosophy that have influenced me, but here I'm focusing specifically on Buddhism and Taoism.

First I'll do a bibliography, then I'll do an index of concepts.

Journey to the West

It's hard for me to describe exactly why, but I've always been fascinated by this story. I guess in part because of how ubiquitous it is, without many Americans necessarily realizing it. It heavily influenced the early Dragonball stories, and by extension many anime and videogame characters. It's been an influence throughout Chinese fiction. There's something very archetypal about it. It's got the kind of gonzo, borderline science-fantasy stuff that I love about Chinese mythology, although it's technically fiction and not mythology. You've got gods and devils with crazy transformations and superpowers, magic weapons, martial techniques, magic sutras, interesting and morally ambiguous characters; it's good stuff. It also deals with Buddhist themes and is a satire for its era.

If I'm being honest, I only ever read the first volume of the

four-volume translation, and that must have been 15 years ago at this point. The first volume is mostly a self-contained story, basically Sun Wukong's origin story, and near the end, it becomes the prologue for the true journey. I regret not reading the full thing, but if I'm being honest, it's... tough. The problem is that the book really leans in HARD on satire of specific things that I just have no frame of reference for; either linguistically, culturally, or temporally. I can respect in particular how it critiques the interplay between Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism in China. I think that's the thing that I found most interesting, aside from the gonzo fantasy of it all. While it's unlikely that I'll ever read the full thing, I could see myself one day reading

The Monkey and the Monk, an abridged version of the story by the same translator. Generally, I hate to lose that context, but frankly, the context was mostly lost on me anyway, so if it's between never reading it, or reading the abridged version, I think that's what I'll have to do.

Dhammapada

One thing that made getting into Buddhism a little trickier for me than, say, Taoism, is that there are many different branches, and even within any given branch, there is not necessarily one single book to turn to, like Lao Tzu's Tao Te Ching. While I'd read various sutras and scholarly articles and such on Buddhism, I only just recently read

The Dhammapada. What's nice is that this version I linked in particular provides a lot of context for the book, why certain translation choices were made or not made, differences between versions of The Dhammapada, differences between different versions of Buddhism, etc. It felt like a good introduction, although I can't speak to that authoritatively. My understanding is that The Dhammapada is a collection of sayings from Siddhartha Gautama, the original Buddha, and so I guess this is the closest thing to a Source of Truth.

I was worried going into this book, that I would come to realize that a lot of my conceptions of Buddhism were wrong, or that I had fundamentally misrepresented some facets. Fortunately for me, I don't think that is the case. Like many theological or philosophical texts, there's a lot of room for interpretation. I don't necessarily strictly agree with everything. There's definitely a bit of self-confirmation; I'm reading into it a particular interpretation based on what I want to believe. I'll go more into the particular ideas in the concepts index, although a lot of it is just taking stuff from the index in this book.

In brief, one thing that I like about Buddhism is that it's actually kind of nihilist, more in an abstract sense than in the very loaded, specific sense in western philosophy which is its own can of worms. I think a lot of Americans have this very New Age-y, whitewashed idea of it, and it certainly can be interpreted that way to some extent, but actually, a big premise of Buddhism is that the material world is this entropic, dysfunctional system, and true happiness comes only from breaking free of this broken system.

The Awakening of Faith: The Classic Exposition of Mahayana Buddhism

As I said before, it's tough picking out the best primary sources for Buddhism. I was led to believe

this book is a good primary source for Mahayana Buddhism, one of the main branches of Buddhism, which was the version that initially spread in East Asia. Given my prior affinity for Taoism, and my appreciation of the satire and interplay of these ideas in Journey to the West, I was more so inspired by Buddhism within the context of China specifically, so I wanted to educate myself at least somewhat on that level in addition to primary teachings from Siddhartha Gautama.

I'm still reading this book, but so far I'm enjoying it. As with the translation of The Dhammapada above, this one includes much-appreciated context. I already get the sense that Mahayana Buddhism leans just a bit more into the nihilist or almost absurdist, kind of funny aspects of Buddhism that I like. I think I actually laughed a few times while reading this (to be clear, in a good way). If I'm being honest, I could not off-hand articulate the specific differences between original Buddhism and Mahayana or other branches, that's just a level of minutia that I struggle to care about frankly. I'm just concerned with the ideas, I don't care what lines other people draw so much, except to the extent that I genuinely don't want to overstep or offend, which I realize sounds like a contradiction, but so it goes...

Tao Te Ching

Up until maybe the last few years, I would have considered myself more so a Taoist than a Buddhist (I don't know if I'd really consider myself either, but at least on some level). I had read the Tao Te Ching when I was younger, at a really pivotal time when I was going through some things. I've reread it several times since, but even that has been a while, so it's hard for me to articulate many particulars, although I'll try to do so in the concepts index. I've read several translations, and there are some really bad ones. Unfortunately, I don't remember off hand which translation I've read that I most prefer, but I think I've read

this one before and thought it was good.

Chuang Tzu

This is another Taoist book. I read this several years after the Tao Te Ching, while I was going through another rough time. I only read it the one time, and while it certainly influenced me on some level, I really can't speak to the particulars at all anymore, the influence is sadly no longer a conscious one. I'll have to reread it someday.

Penguin Classics is generally trustworthy in my opinion, as far as translations go.

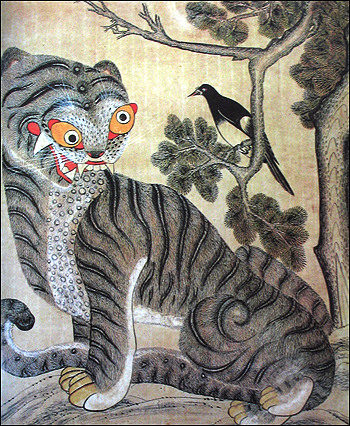

Vinegar Tasters

This allegory holds a special place in my heart for some reason that I can't totally articulate. I think it just does a really good job of encapsulating the relationship between Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. You have Siddhartha Gautama (Buddhism), Lao Tzu (Taoism), and Confucius (Confucianism) each sipping from a pot of vinegar. Buddha says it's sour, it's bad, we need to start over or move on. Confucius says it's bitter, but can be refined, or sweetened, or fixed in some way. Lao Tzu says: guys it's vinegar, it is what it is. Back when I was more so a Taoist I preferred Lao Tzu's take, and to some extent I still do, but I do genuinely think all three are interesting perspectives. There are too many things about Confucianism, even from my minimal understanding, that I don't like, which is why I haven't read as much into it, but in a very abstract sense, the idea of being systematic, one could extend that to just saying, be scientific. I also like how the bureaucratic aspects of Confucianism influence Chinese Buddhism and Chinese mythology.

Several books on the "to read" list

The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation I was not originally interested in this, but I had read incidentally that apparently "Book of the Dead" is actually a pretty gross mistranslation, one that's been kept mainly just because it's taken on its own cultural significance, but actually it's more so a book about Buddhism metaphysics in a more philosophical sense, which interests me much more so.

The Way of the Bodhisattva Another book on Tibetan Buddhism. Several of these books were put on my radar from a list of suggested readings to get started on Buddhism, I no longer remember offhand where I found that list.

Concepts

Unlike the "bibliography", I'm not providing specific links here, just wiki it. For several of these, I focus as much on how it relates to MRD as the concept per se. In many cases, I use more generic terminology in MRD, in part because I wanted to avoid terminology overload, and in part because I wanted to avoid preconceived notions or aesthetics. While someone certainly could use MRD to tell a story more specifically rooted in Buddhist and Chinese mythology, I don't want the terminology itself to impress too deeply on GMs and players at the expense of a broader world.

Karma

Karma is a super-loaded term at this point because so many people have this overly simplistic, New Age-y understanding of what it means, and also because it is genuinely a complicated and multifaceted idea that gets interpreted in different ways within the broader scope of Buddhism. Roughly, it is the consequences of one's actions, but whereas most people equate that to "good actions -> good consequences / bad actions -> bad consequences", my take on it, and the take I use within the game, is that Karma is like Mass. It's the quantity of Material "stuff" you've integrated within you. Perhaps Weight would be a better analogy, since it's also the thing pulling you down, deeper into the Material World's "Gravity". And if the Material World is this entropic, corrupted place, then attachment to it is also this corrupting force. Despite how loaded this term is, and I know this will inevitably confuse some people and become a barrier to entry, I do think it is important to use this one word. It's central to all the other ideas in my opinion, and it's at least somewhat familiar, even if I'm using it in a way that's different than many people may be familiar with.

Dharma

This broadly corresponds to both the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (it's a translation thing, but this is where The Dhammapada gets its name), but also to the phenomenology of Buddhism (although Dharma also exists in Hinduism and Jainism). It seems so broad in its scope, that at least to me, I don't know how useful of a term it is unless you already have sufficient knowledge of Buddhism which I myself lack, so I didn't see the point in including it in the game, but I thought it must at least be acknowledged here.

Samsara

The cycle of death and rebirth, of reincarnation. This is basically the gameplay loop of Karmic Attachment and Reincarnation within the context of MRD. It's a super important concept in Buddhism, and one of the most fascinating in my opinion, and along with Karma I think is one of the most all-encapsulating. However, I decided that within MRD it would probably be easier to just call it the Karmic Cycle since that's effectively what it is, or at least what it is within MRD, and then it's one less term to have to remember while gaming.

Preta

Also translated as Hungry Ghosts, particularly in Chinese mythology. These are the basis for the concept of Poltergeists in MRD. I take a very loose definition of the term, but basically, they're "souls" (in quotes for reasons) that haven't been reincarnated and that have unresolved Karma. The idea that they're "hungry", to me connects to the idea of Attachment, and that's definitely not an accident. By my interpretation, although by no means canon, it's less about punishment for "bad Karma", or at least not entirely. It's a natural consequence of the system of the Karmic cycle / Samsara, independent of right or wrong. I chose the term Poltergeist over Ghost because... in part because I associated Poltergeist more so with the idea of unresolved issues than Ghost, which I see as maybe too generic, but also, it just had a good ring to it. Preta does as well, but then, that's another term gamers would have to remember.

Sankhara

Sometimes translated as Formations, or Conditioned Things. In some ways, this is like the mechanism of what I call Karmic Attachments in MRD. Again, I didn't want to get bogged down in the terminology, especially since I really don't know enough about it and it probably comes with a lot of baggage that people who know more about this stuff than me would inadvertently bring with them. The cognitive neuroscientist in me and the data engineer in me both find this fascinating for thinking about subjectivity, perceptions, and mental models, but I can't really speak to this too authoritatively.

The Three Marks of Existence

Impermanence (anicca), No-self (anatta), Suffering (duhka).

Impermanence I think gets back to that idea I've said about Buddhism being entropic, that everything we construct, literally, mentally, metaphorically, eventually breaks down into chaos.

No-Self I struggle with a bit. On the one hand, and again speaking somewhat as someone who used to study cognitive neuroscience, I agree with the idea that the Self is an illusion; just a useful construct, or an epiphenomenon of our biology. Anecdotally, I've struggled with how to reconcile No-Self with Samsara / the cycle of reincarnation (that's why I put "soul" in quotes in the Preta section), and I get the impression other people struggle with this as well. I think within Buddhism, it doesn't mean that there is no afterlife or reincarnation, but rather that even that metaphysical... "soul", for lack of a better term, is not a true Self, but is also malleable and impermanent. I know that at various points I've had a stronger grasp of this concept, but this is still the one I struggle with the most in terms of its greater implications in Buddhism, even if, as I said, there are other ways in which this makes very intuitive sense to me outside of Buddhism per se.

Finally, Suffering. As I understand it, this Suffering, or perhaps it's argued the root of all suffering, is the discrepancy between how we innately Condition Things (Sankhara) in a world that is by its nature entropic (Impermanence/anicca). This is again where my idea of Karma comes into play in MRD- whatever you're trying to accomplish, whatever game you're playing, it's a losing game; The Only Way to Win is to Stop Playing.

Diyu

Hell in Chinese Buddhism, combining elements of Taoism, Confucianism, and traditional Chinese mythology, with the original Buddhist concept of hell called Naraka. Most accounts of Diyu I've read do put a finite number on it, but that number varies, and I liked the idea of making them Numberless. I like how in Chinese Buddhism, perhaps because of Confucianism, there is this very bureaucratic, ordered sense of the metaphysical world. It also lends itself well to satirization, as is done in Journey to the West. Importantly, the idea of the metaphysical worlds; Diyu and Tian (Heaven), as being bureaucracies, is not meant in the more colloquial/pejorative sense that one might be inclined to assume, although again, the satire leans into this, rightfully so. To me, it's more a matter of thinking about things systemically. So The Numberless Courts of Hell are an example of rigid, dysfunctional bureaucracy; bureaucracy for its own sake. The Celestial Bureaucracy, at least prior to the ascension of Sun Wukong (The Monkey King), is the idea of a functional, adaptable system- the ideal form of a system.

Admittedly, this is where I take a very different interpretation from Journey to the West, where in that case, if anything The Celestial Bureaucracy was already being represented as fallible (although not necessarily entirely dysfunctional), and Sun Wukong, though still ultimately more flawed, was in some ways provoked by the system itself. I'm still undecided, if I'm being honest, on what stance I want to take on Sun Wukong and The Celestial Bureaucracy exactly. I am pro-systems thinking, but that is very different than being pro-bureaucracies as they exist in practice. It's like the difference between being a critical thinker or scientist, vs. believing in "law and order".

Tao

Pronounced more like Dao, translates roughly as The Way. While it's obviously more so relevant to Taoism, as I've said before, I was actually originally more interested in Taoism than Buddhism, and anyway it's the historical interplay of those two along with Confucianism, that has inspired MRD more so than Buddhism or Taoism per se. It's been too long since I've read the Tao Te Ching (pronounced more like Dao De Jing, as I understand it) to fully articulate all the particulars of it, but I love the concept of Tao. I get the impression that a lot of western thinkers struggle with it, more so than Buddhism which can at least kind of be interpreted in a way more consistent with western thinking. I mean, I kind of think the East/West dichotomy gets overstated anyway, but here I do think it matters.

So as I said with Vinegar Tasters, there's a version of Tao that's more about "the balance of nature / the way of things" that maybe works in a new age-y way, and I do enjoy that side of it. But there's also this side of the Tao that's about reconciling seemingly contradictory concepts, of non-binary logic, of deconstructing conscious thought, of Wei Wu Wei (action through inaction). Within MRD, I think this is maybe the answer to the inevitable question: If the only way to win is to stop playing, why play at all? While ultimately you need to divest your Karma and detach from the Karmic Cycle, because all exertion is Impermanent and attachment is Suffering and true Awakening comes from the acknowledgment of No-Self, there are also real problems in the world that affect people, and even though philosophically we can acknowledge the bigger picture, there's a more literal kind of suffering that it would be nice if we could get rid of in the meantime. From a software engineer perspective, it's sort of to me like how you have to reconcile on the one hand that there are times you need to refactor your codebase, but that takes a lot of time and effort, and in the meantime, you need to maintain and extend the current codebase, and maintaining this balance requires a degree of compartmentalization, and an ability to enter a Flow State. It's a bit more nuanced I think, than a lot of western thought, and requires one to acknowledge different scopes of a problem and how they interrelate and to not lose sight of the forest for the trees.